Art & Identity: The Story Of An Iconic Chinese-Australian Photographer

The renowned photographer, performer, and storyteller tells all

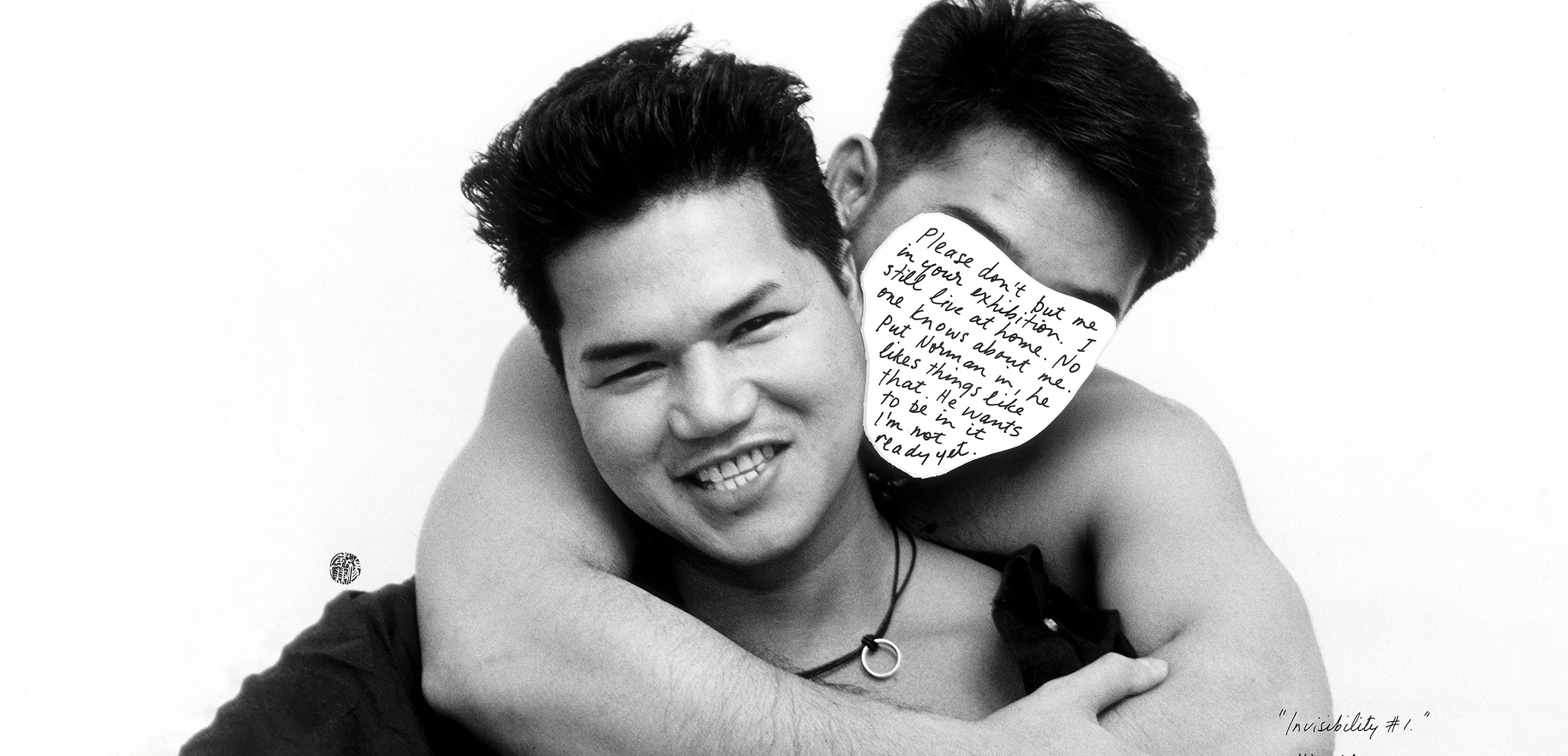

Growing up in a Chinese immigrant family in North Queensland, moving to Brisbane, and then coming out as a gay man in Sydney, renowned photographer, William Yang, captures the shifting cultural and political pressures he faced growing up. We spoke to William about how his work is rethinking the minority status and visibility of minorities as a whole.

Hi William, you were born in Mareeba, Queensland and now work in Sydney. Can you tell me about what your life was like growing up in Mareeba?

Although I was born in Mareeba, North Queensland, I grew up in Dimbulah – a nearby smaller town. Dimbulah didn’t have a hospital. We were the only Chinese family in the district, although I wasn’t aware of my Chineseness until I was about six years old. One day one of the kids at school called me “Ching chong Chinaman, born in a jar, christened in a teapot, ha ha ha.” I had no idea what he was talking about, so I went home to my mother and said, “Mum, I’m not Chinese, am I?” My mother looked at me very sternly and she said, “Yes you are.” Her tone was hard, and it shocked me. I knew in that moment being Chinese was like a terrible curse and I could not rely on my mother for help.

As a gay man from a Chinese immigrant family, what were some of the cultural and political pressures you faced while growing up?

I always regarded myself as Australian and that was the way my mother brought us up – to be more Australian than the Australians. When I went to high school in Cairns, I was much more aware of being racially different in a negative way. The way that I dealt with my ethnicity was to completely deny it. I identified with being Australian. I moved away from racial taunts, and I shut down any conversations about my Chineseness.

I knew from a very early age that I was attracted to men. I knew that this was not the norm and so I always hid it. I never fully articulated this attraction even to myself. One day in Cairns when I was about 16, I read the afternoon newspaper and there was an article about homosexuality. It described what the condition was, and it named three famous ones in history. When I read that I thought, oh God, there’s a name for it. I didn’t know a single gay person with whom I could confide. I thought there were four homosexuals in the world – Oscar Wilde, Michelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, and me.

You’re renowned for your photography of Australia’s LGBTIQ+ scene in the late 70s and 80s through to the present. How have your depictions of this scene changed over the decades?

In the 70s, when I came out, I was still a beginner in terms of photography. They were interesting times and I wish I had my time over again to photograph it. Not many people were photographing then. The main aim of the movement was to have homosexual acts decriminalised, and this happened state by state, beginning with South Australia in 1975 and ending with Tasmania in 1997. But behind this political movement was a huge social transformation. People were coming out, and there was a recognition among gay people about who we were, and an awareness of a gay subculture. With the marriage equality survey in 2017, the numbers favouring gay marriage were 61.6% for to 38.4% against. This indicates a huge shift in public attitudes, and I am glad to witness this change in my lifetime.

The media industry is only now showing more people of culturally, ethnically, and sexually diverse backgrounds. As a Chinese-Australian whose photography raises awareness about social issues, did you face any challenges or receive criticism because of this standard?

In my performance pieces which I began in the late eighties, I use spoken word, projected image and music. I was one of the first Chinese Australians to talk about what it is like to be non-white and gay in the predominately British/Eurocentric Australian culture. People told me it was the first time they had heard an Australian story told by a Chinese person. Gradually, there have been more Asian voices. Now, I am part of an organisation called Contemporary Asian Australian Performance and we aim to develop, nurture and champion Asian Australian performance artists.

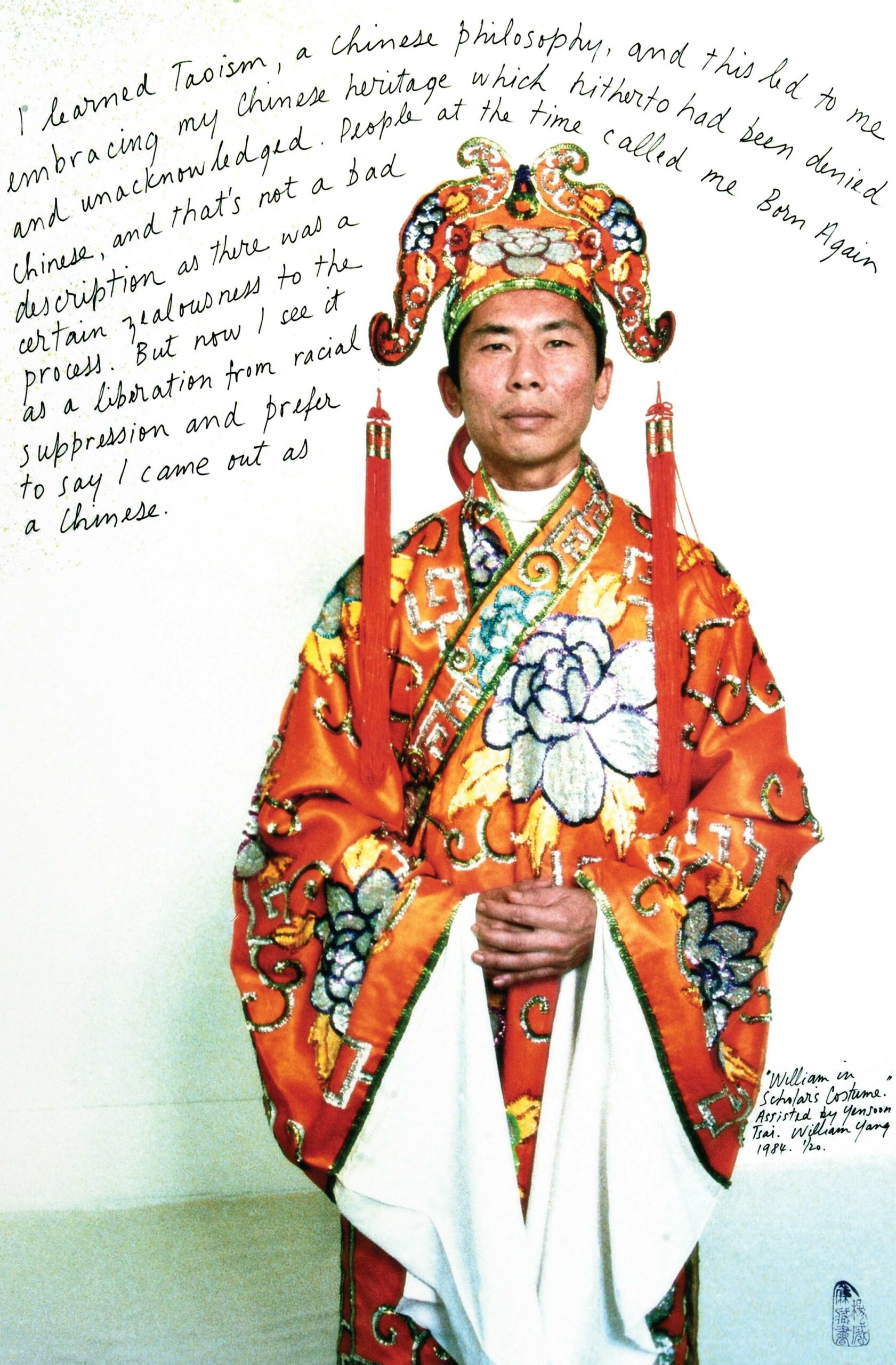

How has your Chinese heritage influenced your work as a photographer in Australia?

I spent 15 years as a freelance photographer in the mid-70s and 80s and part of that time as a social photographer rubbing shoulders with the rich and famous. Now and then, I glimpse back at this world but at the end of the day, I remind myself that these people lived in a different world to me. Don’t get me wrong, I like my photos of celebrities and people want to see them. However, during this time in the eighties, I had an experience where I embraced my Chinese heritage and somehow, I felt that ‘Chinese people in Australia’ was a subject that I should pursue. When I started telling family stories, people liked them. I began to get offers to tour my performances overseas. So that’s when I knew, there was a demand for these stories.

Missed the chance to see William’s Seeing and Being Seen exhibition at GOMA? Explore more of his inspiring work here.